Understanding the competitive dynamics of an industry is a critical part of any growth strategy effort. The metalcasting industry can be analyzed from an overall strategic perspective using the well-known "Porter's 5 Forces" as a useful starting point.

Determining a company's business model, both the current model and the desired model, is also a key part of a growth strategy. Having a grasp of the foundry industry's competitive dynamics, as well as an understanding of business models, lays the foundation for building robust growth strategies capable of sustaining long-term growth.

Metalcasting industry analysis

Developed first by Michael E Porter in 1979 at Harvard University, "Porter's Five Forces" is now a bedrock tool used by business strategists. Especially useful for understanding the competitive intensity of an industry, Five Forces helps define the environment in which a company must find, grow, and protect its profits. Following is a summary of Porter's Five Forces applied to the metalcasting industry. This is a general overview that would be applied on a customized basis for a particular foundry.

In the U.S. metalcasting industry, perennial overcapacity compared to demand has given casting buyers huge bargaining power. Also, fast-growing capabilities of overseas foundries coupled with lower costs in sourcing from Low Cost Countries have given significant advantages to casting buyers. Over the past decade, consolidation of casting-consuming OEMs, especially as they centralize and leverage increasingly sophisticated global supply chains, is perhaps the single biggest development giving the advantage to casting buyers. My company estimates that less than 200 companies consume more than 50% of all castings, by value, globally. It seems fair to say that customers of castings have very high bargaining power overall in the industry.

Force 2: Supplier Bargaining Power

Force 2: Supplier Bargaining Power. As raw materials, consumables, and specialized equipment are key requirements for metalcasting, understanding the suppliers' bargaining power is important, too. In addition to the number of suppliers, bargaining power is influenced by availability, unique performance attributes, service capabilities, and a foundry's cost of switching, to name a few factors.

Even more so than consolidation of customers, the U.S. foundry supplier base has shrunk dramatically over the past two decades. Consumables and equipment suppliers specific to foundries now number only a few for any given material or specialized equipment. Suppliers of commodity metals, scrap, alloys, and the like, price and supply on a global basis. Often, other sectors drive the pricing of these materials, as foundry consumption is small by comparison. Even the supply of sand has become problematic for foundries, with the competition for limited sand supplies from the shale-gas fracking markets.

Here, too, it seems fair to say that suppliers to foundries have high bargaining power overall. Generally speaking, it is no wonder many foundries feel they are between a rock and a hard place, given the bargaining power of both suppliers and customers!

Force 3: Intensity of Competitive Rivalry

Force 3: Intensity of Competitive Rivalry. How many competitors do you have? What are their relative capabilities compared to yours? This is perhaps the most critical factor to analyze, carefully and objectively. Yet, it is often overlooked or not well understood by most foundries. Granted, some metalcasters do have such a well-developed, differentiated, and protectable position that they have few competitors – perhaps investment casters of jet engine blades fit this category. In the slow growth market of the U.S., there has been a significant number of closings and consolidation of foundries as well. This can lead, and has led, to less competition. However, the consolidation of the customer base, coupled with a proliferation of Low Cost Countries' competition has kept foundries' competitive rivalry high.

The ease of entry for new competitors in the foundry industry is an interesting one in the U.S. Heavily influencing ease of entry for several decades has been the over-supply of readily available cheap equipment from shuttered foundries. Likewise, entire bankrupt foundries available at a small fraction of the initial investment seem to be a recurring theme.

This situation may be changing, finally. Even old foundry equipment eventually cannot be repaired, or it becomes technically obsolete. Also, new foundries are almost impossible to get permitted in the U.S., and existing foundries are hitting their air permit and other regulatory limits. Indeed, in many casting markets domestic supply seems currently to be very tight, with lead times increasing dramatically.

Unfortunately, huge amounts of new casting capacity have been added internationally. Especially in China and India, substantial new capacity has been built. Costs are inherently lower, and will remain so. While the bulk of output from these foundries is thankfully consumed in their home markets, the potential of availability in the U.S. market is significant. Especially if there are significant slowdowns in their home markets, imported castings would pose significant competitive threat.

Force 5: Threat of Substitute Products. There is, and always will be substitution of one material for another, for example plastics instead of metal for some components. Likewise, there always will be the rivalry offered between metal choices, for example, iron versus aluminum. Alternatives to making a metal component via machining and weldments, via forging, via powdered metals, etc., are part of the strategic discussion for metalcasters. Fortunately, major changes in materials take enough time for metalcasters to proactively adjust. Likewise, there are ample opportunities pursued by pro-active metal casters that counter substitution, such as converting weldments to castings.

Foundry Business Models

I prefer a simple but elegant definition of ‘business model' – how an organization captures and sustains a commercial opportunity associated with a casting. With this in mind, we can discuss the two basic business models for foundries: Jobbing and Captive. There also are two additional important variations: Independent Foundries with a Market Focus, and Semi-Captive Foundries.

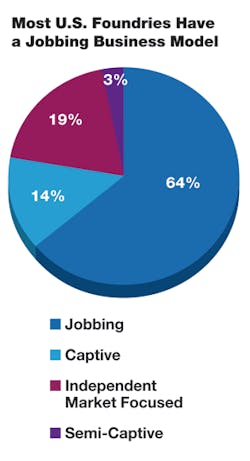

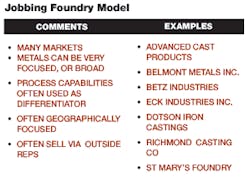

Jobbing foundries pre-date the Industrial Revolution, and probably even pre-date written history. Simply stated, a jobbing foundry produces whatever job shows up at its doorstep, within its capabilities of metallurgy, size, etc. The critical factor historically has been the ability to use a rough sketch, a broken part, or even a complete set of engineering drawings, and make the mold and method it. The artisanal skill to make the mold, combined with technical capability of metallurgy and foundry practice, was enough to set up and differentiate a foundry. Even until recent times, this market was defined mostly geographically. Indeed, many foundries took on the name of the town in which they were located. About 64% of all U.S. foundries are estimated to fall into the Jobbing category.

Jobbing foundries capture commercial opportunity primarily via a capabilities perspective, making the capabilities available to anyone requiring them.

I prefer a simple but elegant definition of ‘business model’ – how an organization captures and sustains a commercial opportunity associated with a casting. With this in mind, we can discuss the two basic business models for foundries: Jobbing and Captive. There also are two additional important variations:

Independent Foundries with a Market Focus, and Semi-Captive Foundries.

Jobbing foundries pre-date the Industrial Revolution, and probably even pre-date written history. Simply stated, a jobbing foundry produces whatever job shows up at its doorstep, within its capabilities of metallurgy, size, etc. The critical factor historically has been the ability to use a rough sketch, a broken part, or even a complete set of engineering drawings, and make the mold and method it. The artisanal skill to make the mold, combined with technical capability of metallurgy and foundry practice, was enough to set up and differentiate a foundry. Even until recent times, this market was defined mostly geographically. Indeed, many foundries took on the name of the town in which they were located. About 64% of all U.S. foundries are estimated to fall into the Jobbing category.

Jobbing foundries capture commercial opportunity primarily via a capabilities perspective, making the capabilities available to anyone requiring them.

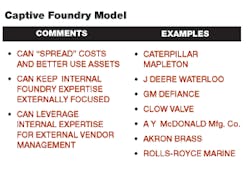

However, few truly captive foundries remain as OEMs. Adequate sourcing from a plentiful and more capable external supply base has led to the spin off or closure of most captive foundries. Today, captive foundries comprise an estimated 14% of the U.S. foundries.

Captive Foundries, continued...

Captive foundries are still very much required in many emerging markets, where the alternative of buying castings externally is not readily available. In the U.S., captive foundries are generally surviving due to legacy requirements or to produce a limited percent of truly mission-critical, hard-to-find, or truly proprietary parts. In some cases captive foundries do offer leverage over independent foundries to allegedly make a decision, "make or buy."

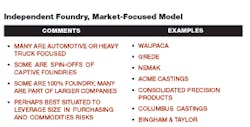

As compared to jobbing foundries, the independent, market-focused foundry operations tend to have far fewer, but larger, customers, and tend to be more externally focused on commercial requirements. Technical requirements are more focused, specifically to meet the targeted market requirements.

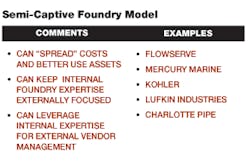

It is hard to judge the merits and success of semi-captive foundries accurately. However, it seems fair to conclude that these foundries are not generally in long-term growth mode.

Evaluating a specific foundry's operation within the context of one of these four basic business models can derive a great deal of insight. Much can be learned from understanding how other companies in the same category have positioned themselves in the competitive environment. This is an obvious exercise to understand direct competitors. Perhaps more important is the insight that comes from understanding other successful metalcasters for ideas to help with strategy.

Mike Swartzlander is the Managing Director of Cast Strategies LLC, which provides consulting services on growth strategies to manufacturers in the metalcasting s, specialty chemicals, and composites parts markets. Visit www.cast-strategies.com.