According to the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics, the most endangered species in the U.S. ecosystem is the “locomotive firer”, a person who monitors instruments on trains and watches for signals and other incidents that may impede smooth railway operation. Such workers numbered 1,200 in 2016, but by 2026 that total is forecast to decrease to just 300, a decline of almost 79%.

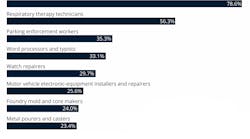

Other job categories also are disappearing, including respiratory therapy technicians (-56% by 2026) and parking enforcement workers (-35%.) Moving down the list past watch repairers and motor vehicle electronic-equipment installers/repairers we find foundry mold- and coremakers (-24%) and metal pourers and casters (-23.4%.) I have written in the past about the demise of certain job categories and what it particularly means about metalcasting, but the problem is not confined to metalcasting. There are many observations to be made – about the pace of economic development and the inevitability of technological change, and I aim to be realistic about this. It’s my belief and frequently stated position that employers would readily embrace a system in which there are no human subordinates, just systems or machines that execute assigned work as instructed, with no further expectations, risks, or liabilities. I believe this because I realize that most employers also operate with a realistic (that is, without sentiment) view of their enterprise: It must perform. That is all .

This does not mean there is not or should not be any sentimentality in our working lives. In metalcasting particularly there are many business owners, executives, and managers who are devoted to their business and their employees. And there are many people employed in the business who are committed to the work they do, and the enterprises and colleagues they where they serve.

This sentimentality is a problem, not because it devalues our work but because it challenges the emerging reality. Without some clear explanation or indication of a change in the trend, each of us is likely to see ourselves listed with the locomotive firers on a future list of endangered species. And each of us will be surprised when that reality is uncovered.

Over the past several months General Motors has been under steady criticism for its decision to close four large plants, the most notable of which is the Lordstown (OH) Assembly Plant. GM has many problems to address in order to strengthen its enterprise, to make it “perform,” and there is no clear role in the foreseen GM for Lordstown’s output of internal-combustion engine-powered compact cars.

Last month word spread that GM had a buyer for Lordstown that would build a new line of electric vehicles there, though the details are vague and the benefits to the now ex-GM workers are hardly commensurate to the formerly steady, high-paying and demanding work they are unnecessary to perform.

Of course, the finality of GM leaving Lordstown is notable and pitiable, but it’s not unforeseen. The complex has been downsizing and under steady evaluation for closure for decades. Politicians have twisted arms to keep GM in place and wheedled workers to support their efforts – to the predictable end that this closing and the human cost are being evaluated mainly now for the political effect. “Who will pay the price for GM’s cruelty and the workers’ suffering?” is the basis for our understanding of the situation.

Our understanding of the situation has to expand – but how? Since the establishment of tradesmen’s guilds in medieval times individuals have learned to incorporate their work as a part of their identities. Many people bear names that reflect the work of long-departed ancestors. Working for GM helped these men and women know where they belonged, and gained them recognition from powerful individuals and institutions. For everyone, work shapes self-esteem and directs our ambitions.

It’s not the same everywhere in the world. There are successful economic systems in which the work of employees is intolerable or unacceptable by our now-fading standards, but we have no reply to incremental changes to our system that evaluate reliability over performance. And so we grow sentimental about lost work because we recognize that loss means the sacrifice of individuality.