The unrelenting pace of technological development is having an undeniable, if not entirely definitive, effect on individuals assigned to operate new machinery, processes, and systems. One recent study showed 55% of manufacturers admit there is a skills gap between their workers and the systems they are required to use, up from 38% in 2013.

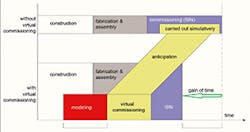

And, while technology may be the source of an expanding need for training, technology is also being applied as a solution, or a bridge, to fill in the gaps in individual skills. When new operations are in the trial and start-up phase, “virtual commissioning” makes it possible to test and verify the functions of automation systems and to optimize process controls and process steps before “actual” commissioning takes place.

A series of improvement projects at the Gienanth GmbH iron foundry in Eisenberg, Germany, demonstrated how commissioning could be shortened by simulating the equipment and functions in advance, in a “digital factory” according to Küttner Automation.

There is more to this approach than simply developing operators’ skills. During modernization or rebuilding, every day of lost production time has an effect on overall productivity. Once a plant is out of service, everything possible is done to restore operations as quickly and smoothly as possible. But, the engineers and programmers involved in these projects frequently need more time for commissioning due to unforeseen delays during installation. As such, the success of a revamp project largely depends on how quickly and reliably the hardware and control software can be tested and optimized.

Küttner Automation has developed “virtual commissioning” to reduce commissioning times and accelerate ramp-ups. The process involves creating a testing environment in which all mechanical, hydraulic, pneumatic and electrical components of the control systems are connected in a “digital factory.” This simulation scenario allows processes to be optimized and faults in the functional sequence to be identified and corrected in advance, that is, prior to the on-site installation. As a result, all automation sequences have been tested and approved before the new plant goes live.

Actually, the control equipment is commissioned in a virtual environment very early in the project, in parallel with manufacturing and assembly of the machinery. This means no testing and fine-tuning of the control software under time pressure, as is very often the case when these activities take place during the “real” commissioning. In this way, on-site commissioning tasks can concentrate on the signal and field level. According to Küttner Automation, this virtual approach often results in a shorter ramp-up phase by identifying and correcting failures and work stoppages.

Friedhelm Bösche, director of software development at Küttner Automation, always offers virtual commissioning as an option for modernization projects. “Simulating the preliminary commissioning involves some effort in the beginning,” he allowed, “but this pays off later on in the form of major time savings. We know from a great number of projects that the time needed to commission the real systems can be cut by up to 75% when the software has been pre-tested in a virtual commissioning scenario.”

One of the virtual projects conducted for the Gienanth foundry involved a sand preparation plant. Küttner Automation supplied the automation systems, including pre-testing in a virtual commissioning environment.

Roland Walter, project manager for the project, confirmed, “we met all deadlines, although we only had two weeks’ time for the commissioning. The virtual commissioning made us confident at a very early stage of the project that the processes would run as desired. Our production staff were given the opportunity to give input and test the sequences beforehand (and) this has contributed significantly to a fast commissioning process.”

This is an example of technology paralleling human activity. Lately, technologies are applied to get inside the heads of individuals as they work, essentially synchronizing the human thought processes with a production system. Tobii Pro develops “eye tracking” technology, which monitors eye movements as a way to detecting patterns or tendencies, or abnormalities, and to evaluate the implications of that information. It’s used to study how people interact with text or online documents, and in a new development called Tobii Pro VR Integration it’s used to augment skills training in virtual reality settings.

The eye tracking devices collect insights to specific workers’ tendencies and responses, and makes it possible (using VR) to train workers in simulated environments that would be too costly, risky, or difficult to conduct in real life. The skills of the best workers can be identified and analyzed for training others. In short, manufacturers can study and teach how workers should properly use machinery in a safe, virtual environment.

An approach like this can be used for more than training. Henkel, the chemical and lubricant manufacturer, working with automaker PSA, developed a remote-assistance program using customized “smart” glasses, a camera and microphone, to connect PSA workers with Henkel’s technical service center in real time. The expert can be virtually on-site to provide advice on any problem in production.

In many cases the skills gap facing manufacturers is an opportunity to put the right technology in the right place, in the right hands, or minds.

About the Author

Robert Brooks

Content Director

Robert Brooks has been a business-to-business reporter, writer, editor, and columnist for more than 20 years, specializing in the primary metal and basic manufacturing industries. His work has covered a wide range of topics, including process technology, resource development, material selection, product design, workforce development, and industrial market strategies, among others.