FM&T Hall of Honor 2012: The Value of Lessons Learned

Looking back over the lives and careers of the influential metalcasting leaders that make up the FM&T Hall of Honor, one runs into a lot of old-fashioned and retired notions. Notions such as the benefits of hard work, company loyalty and above all an enduring dedication to quality production.

Year after year, stories of these inductees teach the lessons of how traits like these have helped innovate the industry and inspire new generations of foundry workers to carry the torch of this age-old field.

Every new inductee to this exclusive club, however, marks another leader, another innovator, another master of the craft who has left the industry behind after a long, inspiring career. As these men leave and the generation of workers they influenced age closer to retirement, the foundry is facing a pending crisis: the newest generation of workers is entering the rebounding industry without the benefit of these leaders or their old fashioned notions to guide them.

Luckily, though, this new generation has Robert Smillie.

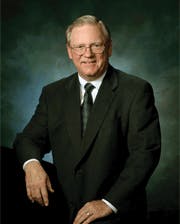

With his 35 years at Ford Motor Co. and eight more at Nemak Corp. of Canada, Smillie is every bit the industry leader this Hall of Honor was designed to celebrate. However Smillie has not quite left the industry yet, and he is not likely to in the near future.

Since leaving Nemak in 2008, Bob Smillie has dedicated himself to giving back to his industry by putting his 42 years of experience to use teaching new generations of foundry workers how to pick up where his generation left off.

"When I started in the foundry, I was thrown in with the wolves," Smillie recalls. "What really helped me was that I had some great mentors that befriended me and were able to help me learn how to make castings at a very early age. What I'm doing at this point of my life and my career is spending tremendous amount of my time with students, particularly Foundry Education Foundation students to give back some of the knowledge I received as a student."

"It's kind of full circle for me," he said.

As a former FEF president and current member of the board, Smillie teaches high school students about metalcasting at FEF schools in Michigan and Canada, even working with them in the lab and giving them testimony about his life in the foundry, said Bill Sorensen, executive director of FEF.

"Students look at Bob with awe because of everything he has accomplished," he noted. "It's remarkable. He is exactly the kind of person you want on your board."

Taking a look back at Smillie's career, it is no surprise that he should end up in this role. For Bob Smillie, education is at the absolute heart of life — to him, every new opportunity is just another chance to learn something new.

Appropriately, when he started out back in the 1960s, he wasn't exactly sure what he wanted to do or where he wanted to go. He just let his eagerness to learn and his passion for new challenges guide him.

"I was always interested in getting into the automotive side of business," he remembers. "My dad had been in the industry all of his life, so I grew up in that environment and wanted to make that environment my career. I just wasn't sure what that looked like."

This goal, however uncertain, was clear enough to set him off to Kalamazoo, MI, to study mechanical engineering at Western Michigan University.

While there, though it certainly wasn't in his engineering curriculum, he happened into an introduction to metalcasting course -- a class that would change his life forever.

"There I was, a young guy, 21 years old, walking into the foundry for the first time," he recalled. "I saw this fire, all of these sparks. To me it was like the Fourth of July. Why wouldn't I want to be a part of that?"

The whole process of foundry work amazed him. The transformation of raw materials to iron to product set in motion a lifelong passion for the industry that he still hasn't been able to shake.

"Metalcasting was my first love and remains that today," he said. "I still have that same wonder."

Smillie embarked on his career without hesitation, spending the whole of his senior year down on the floor of Ford Motor Co.'s Dearborn Iron Plant as a co-op student worker.

After two terms of that assignment, he was hired on full-time at the Dearborn plant as a Ford College Grad Trainee — a position that gave him a full tour of foundry life before settling in as a degreed engineer. He wouldn't stay settled for long.

Within six months in the engineering office, he was called back out to the factory floor to fill in for an absent supervisor. He never really made it back to the office after that.

"From that day, I never came off the factory floor again," he said. "True manufacturing was really my calling. I made that my job for the rest of my career."

Two factors drove this career: his passion for his work and an unquenchable thirst for knowledge.

"I was always an inquisitive person. I loved challenges," he recalls. "I never turned down an assignment no matter how difficult it seemed, no matter what shift it was on, no matter the circumstances. If I saw it as an opportunity to learn new tools to put in my toolbox, if I saw it as an opportunity to learn some new metal casing process, I took the assignment. That enabled me to move along through the organization very quickly."

The challenges Smillie faced through his career were sometimes fierce, sometimes daunting, but this ebullience never failed him, he said.

The full manifestation of this began in the mid-90s when Smillie took over the production manager's position at Ford's Cleveland Engine Plant One during a time when the company was building its second engine plant in the area.

Both Smillie and his boss, Gifford Brown, had been introduced to the principles of lean manufacturing previously and both had seen it in action in Japan. They saw the building and design of Cleveland Engine Plant Two as a chance to finally implement at last some of those principles at Ford. The only problem, of course, was that neither of them had ever done anything like that before.

That made it a perfect challenge for Robert Smillie. It was just another opportunity to learn.

"Every Friday afternoon when things were winding down and people were getting ready to go home, Gifford Brown and I would meet in his office to talk about lean," he recalls. "He had a huge library of books regarding elements of lean manufacturing. He would walk over, pick out a book and read a chapter. Then I would read a chapter and we would talk, just the two of us, an open dialog over what it all really meant."

All those lean principles that he and Brown hashed out in those two-person study sessions were implemented at the Cleveland Engine Plant Two, making it Ford's first truly lean powertrain plant.

The result of their effort was an inarguable success, winning the coveted Shingo prize for Excellence in Manufacturing in 1996.

After 35 years at Ford fighting for these kinds of successes, and learning lessons across the industry, Smillie officially retired in 2001. That retirement didn't exactly stick, however.

"They retired me on a Friday and on Monday I was working for Nemak as Vice President of Canadian Operations in Ontario," he laughed. "Many of my friends are retired, but I doubt I ever will be," he said. "That's just who I am."

Since leaving Nemak in 2008 to start his own consulting firm, RWS Productivity and Quality Solutions, Smillie has dedicated himself to giving back to the industry.

"Robert has shown an unwavering support for the Foundry Education Foundation," offered Doug Trinowski, AFS Division Council Chairman. "He is absolutely committed to the education and development of young people in the foundry industry."

This dedication has had a dramatic impact on the next generation of foundry workers, he noted.

"He has had an impact both within Ford and Nemak and through the further reach of FEF, which goes beyond the reach of a particular company," he said. "It reaches the whole metalcasting industry and prospective engineering students throughout the U.S. and Canada."

"There is a lot of young talent that we need to develop and nurture and get them set up for success," Smillie maintained. "If they have the right attitude, if they are willing to take some risks, come in with an open mind, I really feel that they will be able to write their own legacy."

It is that hope, he said, and not the rewards of his career, not the long list of honors and awards he has received, not even his honorary Ph.D. from the University of Windsor, that keeps him active in the industry today.

"There is just always someone else that we can help educate," he said.