Metalcasting Growth Strategies III: How to Grow When the Market Doesn't

Foundry overall is a slow-growth market. Generally, the industry is very competitive, leading to low profitability and financial instability for many foundries. Nonetheless, long-term sustained and profitable growth is achieved by some management teams even in this challenging environment. How do they do it?

Defining a unique and differentiable position at the core of a company's business is paramount to creating a solid foundation for profitable growth. Once defined and well understood, identifying business adjacencies that offer promising possibilities for profitable growth can be identified, prioritized, and resourced. If chosen properly, progressing into these adjacencies not only will leverage the core, it also will protect, strengthen, and ultimately expand the core. This tool-set growth strategy has been well described by Chris Zook and James Allen, in Profit From the Core, published by the Harvard Business School Press, 2001.

Here, our attention is on the concepts of 'core business' and 'adjacencies,' as well as 'opportunity mapping.' These concepts also are discussed from the perspective of the four basic foundry business models – jobbing; captive; independent market-focused; and, semi-captive foundries (see “How Foundries Make Their Money,” FM&T November 2012, p18.) Subsequent installments will provide some deep dives into various adjacencies specific to foundry businesses.

Defining 'The Core'

The core is best described as whatever provides the most unique and greatest competitive advantage for the company in the marketplace. The core consists of some combination of existing products, existing customers, process capabilities, technologies, market segments, market channels, and geographic coverage that are truly unique and profitable to the company. Critical to defining the core is clear identification of the customers and products that provide the majority of profitability to the business. This is a more difficult task than it seems at first, as the company's management must be brutally honest and unbiased in executing this assessment. Often it is helpful to use facilitators from outside the company, working with the managers to define the core accurately.

I have found it useful to apply the 80% rule to gross profit. This means evaluating first the existing customer base, then the existing product base, to find the combination of customers and products that contribute 80% of a company's gross profit. In most cases, metalcasters find that only a small fraction – 10% or less – of their customers/products yield 80% of the gross profit. Sometimes, the product or process capability or metallurgical capability is truly unique, and this becomes the basis of the core. Frequently for metalcasters, a limited number of customers, perhaps within a well-defined geography, are the core's foundation.

Finding uniqueness that is highly profitable is more important than artificially defining a core bigger than it actually is. Peeling back the onion, the management teams often stop prematurely by including products, customers, process capabilities, technologies, etc., that are not truly very unique or profitable. A smaller, but very unique and profitable core is far more valuable as a starting point for a growth strategy than a larger, but less unique and less profitable core.

Understanding the economics to serve the core becomes a critical part of the core's definition. By carefully assigning all costs truly required to serve only the core, all other costs are, in effect, being used to serve business outside the core. This exercise becomes useful as part of the process of defining business adjacencies and identifying existing resources that could be used to pursue adjacencies in a prioritized manner. Often companies are surprised to discover how much existing resourcing could be made available to pursue adjacencies.

Often an honest assessment of the core of a business provides insight into what I call management “hobby” businesses. These can be the leftover business efforts of past initiatives to grow new business. These might even have been sizable and profitable business pursuits in prior times, but now are remnants of the past. Often sponsored by the owner or CEO, these hobbies can survive without critical assessment of results and without clear expectations on expected outcome. Many times, these hobbies are chronically under-resourced and never can reach critical mass to achieve success. Hobby businesses are fertile ground either to kill off completely, or to move from a hobby to a legitimate business adjacency.

Careful understanding of the true core of a business also allows the organization to free resources from noncore customers and products so as to exploit additional profitability in the core, or work to protect the core. Many times, the core business is left vulnerable by prematurely shifting resources to non-core business, or by new competitive dynamics in the market.

Identifying 'Adjacencies'

Once the boundaries of the core business are defined, attention can be directed to identifying adjacencies. Business adjacencies, by definition, leverage in some way the strengths of the core. Often, making the non-core customers of core products more profitable, and conversely, selling non-core products to core customers provide the quickest way to increasing the core itself. Expanding into new geographies with core products, or leveraging existing relationships with core customers to expand to other geographies where they might operate is a common growth strategy.

Carefully assessing core customer needs in order to find opportunities to provide other products, services, supply chain support, or additional casting processing, or sub-assembly can lead to important, new profitable growth. This might require internal development of new capabilities, or strategic partnering with other companies to address core customer needs. Critical to these efforts is careful examination how not to let the new services or products become simply an expected, free add-on to the core product offering.

A very useful tool in growth strategy is opportunity mapping. Beginning with the core business in the middle of the map, the various themes for growing the business can be shown along different axes. Along each axis, new strategic growth initiatives can be shown in a prioritized manner with the stated intent of expanding the core over a targeted period: three to five years is a typical timeframe.

Expanding a foundry business by forward integration to include processing parts beyond raw castings is a typical path to explore. Forward integration could go well beyond casting processing too, to include subassembly, or even into becoming an OEM! Incidentally, backward integration into metalcasting is an on-going possibility. More than one successful foundry operation has been started as a backward integration by a machine shop into foundry. Even if a foundry chooses not to forward integrate it is an important exercise to explore and understand fully the entire forward value chain, from raw casting to final OEM product, not only to explore growth opportunities but also to look for potential competitive threats.

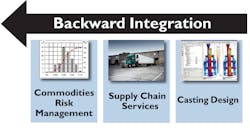

Backward integration for foundries is an area for consideration too, especially if significant competitive cost reduction or risk mitigation is possible. Especially valuable for large foundry operations, backward integration might serve not only as cost reduction and risk mitigation, but offer new revenue streams in their own right by servicing other non-foundry markets, or even other foundry companies.

In considering what makes good adjacencies and how to prioritize and resource initiatives along the adjacencies, it is critical always to keep in mind the core business. The challenges of balancing the correct resources to protect and fully exploit the core and resourcing new initiatives are significant. Concentrating on growing adjacencies that protect the core is as critical as growing adjacencies that leverage the core. Always, the key is to be continually building market power and customer influence. Market power and influence mean building deep customer loyalty and interdependence.

Core and Adjacencies Considerations by Foundry Business Model

In the preceding article of this series four basic business models for foundries were described: jobbing, captive, independent market-focused, and semi-captive foundries. Each of these four business models presents special challenges and opportunities in core and adjacency identification, and subsequent growth strategy development.

Jobbing Foundries especially are challenged to build robust strategies for sustainable long-term growth. By history and by nature, jobbing foundries tend to have a very internally focused growth strategy to concentrate on process capabilities and capacities. Many times, growth opportunity is seen as whatever quotation comes via the Internet or by way of a manufacturer's rep, that the foundry has the technical capability to make. Often capabilities are added as competitive responses to what other foundries already are doing, or what is required by an OEM as part of its RFQ process. Capacity is many times added without a clear business plan to secure long-term, profitable sales from the investment.

Nonetheless, careful examination of a jobbing foundry operation often uncovers a true core business of unique and even significant competitive and profitable market power. While it might be much smaller than the overall business, the core is the most promising place to start to define a growth strategy.

Often, the core in these foundries can be taken for granted. For example, the core business might be replacement parts for decades-old original equipment that was manufactured by a now defunct OEM or, as is often the case, an OEM absorbed by another OEM. Having the tooling and the know-how for these specific parts generates profit far in excess of the more mediocre business done by the foundry. Or, the core might be that the foundry is the “last man standing” that offers a specialized process, say, shell molding, or iron lost foam, or whatever, in a specialized market or geography.

Once understood, the core offers at least the possibility for developing a strong growth strategy. If in fact there is little opportunity to grow from the core, then, at least the foundry knows it must develop a second core, while the first core is still able to fund growth.

Captive Foundries by definition must be internally focused in determining their core business, or, in this case, what it will provide or do to make the parent company uniquely and significantly more competitive. Historically, captive foundries were a natural requirement for an OEM to ensure adequate supply of critical castings, or to provide a very unique casting attribute that contributed to the OEM's overall competitive advantage. In many cases these historical advantages have greatly diminished or have disappeared completely.

Defining a true core for a captive foundry is critical from a number of perspectives, not the least of which is ensuring the parent company's needs are met by continuing to keep the foundry captive. If in fact the foundry operation has a strong core, then understanding the best way to leverage this core for the OEM's advantage becomes the top priority. Managing the foundry within the boundaries of the core to exploit significant value addition to the OEM parent is critical. If no strong core can be defined it might be best to divest the foundry operations, which has been the route pursued by many of today's largest independent foundry companies.

Independent Market-Focused Foundries are by nature externally focused, more so than jobbing foundries. Interestingly, it is fairly common for these foundries to assume what their core business is based on revenue, and not profits. Also, there is a tendency for these foundries to overestimate their uniqueness as well as to misidentify what is really important to their customers. Often, foundries in this category focus mostly on building total casting capacity and reducing costs by economies of scale, in the attempt to gain some critical market share in terms of product category, or leading market share of targeted customers. If positioned in selected counter-balanced markets, these foundries can generate good cash flow on a sustainable basis. However, in many cases, perhaps profitability could be much enhanced and the company better positioned over the long term with careful scrutiny to understand and leverage the true core of the business.

Semi-Captive Foundries might offer the most challenging assignment in determining and implementing growth strategy. Often, it seems, these foundries live in a schizophrenic state without any clearly defined pathway to growth. This might be fine if the primary outcome is the goal of using excess capacity in order to spread the foundry's truly fixed costs, thereby reducing costs to the OEM for its internally produced castings. However, it is questionable that this is truly advantageous or sustainable over the long term in most cases. One approach used by some semi-captive foundries with good success is to purposely carve out a fairly autonomous business unit, resourcing the business to proactively develop a growth strategy for the business, and generate a new revenue stream for the OEM.

Mike Swartzlander is the Managing Director of Cast Strategies LLC, which provides consulting services on growth strategies to manufacturers in the metalcasting s, specialty chemicals, and composites parts markets.

About the Author

Mike Swartzlander

Founder & Managing Director

Mike Swartzlander is an accomplished executive with more than 37 years’ experience and a focus on building and implementing global growth strategies. Prior to starting Cast Strategies in 2009, Mike served as Ashland Inc.’s first Managing Director in India. Previously, Mike served in a number of leadership positions at Ashland, including Vice President of Ashland Inc., General Manager of Ashland’s global castings consumables business and management positions at the company’s composites and electronic chemicals businesses. Prior to Ashland, Mike held management positions at Union Carbide Corporation and the Tate & Lyle Co. starting numerous specialty chemical businesses in the U.S., Asia and Europe.

Mike is a Past Officer of the American Foundry Society, Past President of the Foundry Educational Foundation and remains active in the industry as a speaker and author.

Mike is active in trade associations both in India and the USA, where he has been a speaker on numerous occasions and has been awarded the prestigious Ray H. Witt Management Award twice by the American Foundry Society for presentations at Casting Congresses.

About Cast Strategies LLC: Cast Strategies LLC is a trusted advisor to the global business-to-business castings, chemicals and materials industries, helping companies develop and implement robust strategies to deliver sustained profitable growth. Learn more at www.cast-strategies.com.